According to an article by Jennifer Jacquet on AlterNet, long-line caught hake (left photo) is out there masquerading as tilapia (right photo), the darling of the sustainable fish movement. The endangered shark is being recast as scallops, flounder, or tuna...

So how do you tell what fish is really on your plate?

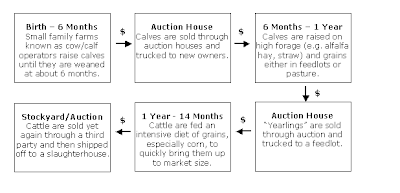

So how do you tell what fish is really on your plate? The beef industry has the technology to trace specific lots or even specific steaks back to a particular farm or cattle. The technology may not be used much except by some of the better natural or organic beef programs out there. But at least it exists.

Traceability for fish seems a bigger challenge. After all, some fish are still harvested from the open oceans, where there aren't any fences.

I personally think the solution for beef (and other meats) is to leverage source-verification technology to provide complete transparency to the consumer. Let us know the breed, where it was raised, how it was raised, what it ate, where it was slaughtered, etc. and let us vote with our wallets to support sustainability or specific farms or whatever criteria are important to us.

Wondering if anyone is trying to offer up a similar solution for fish.